Microbial communities including viruses, prokaryotes, fungi, protists, and microfauna, are critical groups of life in almost all ecosystems on Earth. Soil is one of the most heterogeneous and dynamic environments that provides habitat to, and is shaped by the functions of, amazingly large microbial diversities. Proper management of soil is promising to mitigate global change, promote ecosystem health, support the production of food, fuel, and fiber, and prevent diseases. Our research is dedicated to understanding what microbes do in soil and other terrestrial environments, particularly how they interact with each other, and to develop paths leading to a sustainable future.

Microbial interactions are increasingly recognized as important drivers of community assembly and function, yet challenges remain in quantifying these interactions and their ecological impacts. We aim to understand the principles and ecological impact of microbial interactions in their native environments and develop ways to mitigate global change and promote One Health. The Hawaiian Islands have diverse soil types and climate zones within close distances. It is a perfect model for land-sea transition zones and patchy landscapes, offering a unique opportunity to probe into fundamental microbial ecology questions, including microbial interactions and microbial biogeography.

Distribution and persistence of soil-borne pathogens

Soil harbors many pathogens of public health concern, but the ecology of these pathogens in the context of the soil microbiome is far from clear. Amoeba-associated bacteria Legionella spp. are the causal agents of environmentally acquired pneumonia legionellosis. The exponential increase in legionellosis incidence rates in the past two decades correlated significantly with temperature and extreme precipitation events in the US, implying augmented risks due to interactions between environmental Legionella with climate change. However, how climate change affects Legionella’s abundance, distribution, association with amoeba host, and infectivity have not been systematically evaluated. In this NIGMS-funded research project under PBRC’s Microbiome COBRE, we aim to establish a framework for soil-borne pathogens’ risk assessment based on mechanistic understandings of microbiome (biotic) and environmental (abiotic) controls on their persistence and proliferation. We will test this hypothesis utilizing the broad range of soil types, ecozones, and environmental gradients on O‘ahu, with the first focus on the Waimea watershed highlighted by the Center for MICROBIOME Analysis through Island Knowledge & Investigation (C-MĀIKI).

A postdoc position is open for this project. Visit Join page for more information.

Bacterial-fungal interactions in grassland soils

Bacteria and fungi are dominant soil microorganisms. They drive essential biogeochemical processes. Yet we are still not clear how these two groups interact in their natural habitat, as a community. Our team seeks to understand the fundamentals of bacterial-fungal interactions in their native soil environment, and how they determine the availability and fate of C across the complexity of soil niches, in different soil mineralogies and under reduced water availability. In this US Department of Energy-funded project, we use multi-comics, stable isotope probing, network analysis, modeling, and combine experiments scale from microcosms to the field to understand soil bacterial, fungi, and their functions in California and Hawaii grassland soils. This project is in collaboration with Dr. Nhu Nguyen, Dr. Tai Maaz, Dr. Jonathan Deenik in the Department of Tropical Plant and Soil Sciences at UH Mānoa, Dr. Mary Firestone at UC Berkeley, Dr. Jizhong Zhou at the University of Oklahoma, and Dr. Jennifer Pett-Ridge at Lawrence Livermore National Lab.

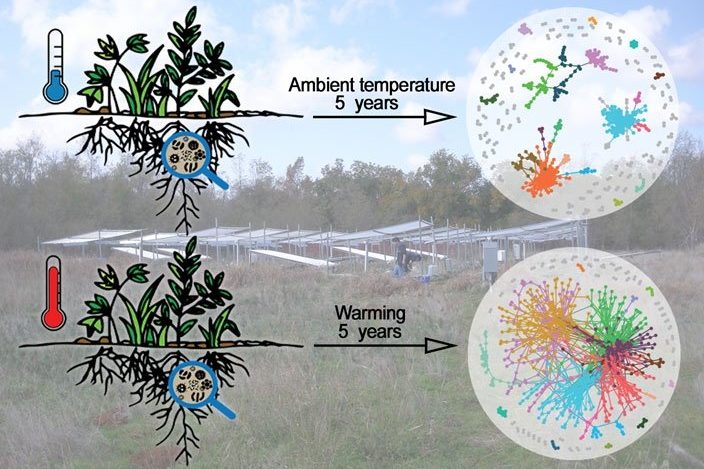

Soil microbial responses to climate warming

Microbes in soil govern the release of carbon into the atmosphere through decomposition. The response of microbial activity to climate change can alter biogeochemical cycles, accelerating or slowing down the release of excess carbon from soil. Long-term data collection from field experiments at Kessler Farm Atmospheric and Ecological Field Station (KAEFS) has informed us a ton on how different components of the soil microbiome respond to ecosystem warming, altered precipitation, and aboveground biomass clipping. Microbes were observed to adapt to prolonged warming as evidenced by decreased temperature sensitivity of respiration, increased microbial turnover rate, decreased microbial diversity, and increased network stability. These ecosystem-dependent microbial responses to climate perturbations can hardly be derived only from edaphic conditions, signifying the urgency of including microbial information in climate models. The treatments mimicking different scenarios of the changing climate have been in place since 2009, and are still under operation – Thanks to our collaborator, Dr. Jizhong Zhou, the Institute for Environmental Geonomics at the University of Oklahoma, and funding from the U.S. Department of Energy! Long-term observations will keep telling us more about soil microbial responses to climate change.

Biogeography of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Root biotrophic arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) mediate the terrestrial geochemical cycle by promoting carbon and nutrient transfer at the plant-soil interface. But what influences AMF community assembly on local and regional scales? Is it host plant species, soil geochemistry, microclimate, land topography, or dispersal limitation? We aim to evaluate the contributions of environmental filtering vs. stochasticity on the composition and beta-diversity of AMF in California annual grasslands dominated by common annual grass Avena spp. We are also developing ways to quantify the patch size of individual AMF virtual taxon to evaluate their ability to disperse. This study is in collaboration with Dr. Erin Nuccio at Lawrence Livermore National Lab, Dr. Anne Kakouridis at Sound Ag, and Dr. Mary Firestone at UC Berkeley.